How the Internet works

Objectives

After this lesson, students will be able to:

- Explain the differences between a client and server

- Explain the difference between the Internet and the World Wide Web

- Explain the significance of an Internet Protocol (IP) address

- Explain how data travels through the internet

- Breakdown the components of a URL: protocol, subdomain, domain, extension, resources

- Identify and describe the most common HTTP request/response headers and the information associated with each

- Create a basic HTML webpage using the most common tags

Internet Acronyms

Working as web developers you will be bombarded with acronyms, but don't worry just like the MRT you don't need to know what it stands for in order to use it.

- WWW (World Wide Web)

- ISP (Internet Service Provider)

- DNS (Domain Name System)

- TCP (Transmission Control Protocol)

- IP (Internet Protocol)

- URL (Uniform Resource Locator)

- TLD (Top Level Domain)

- HTTPS (Hyper Text Transfer Protocol Secure)

- FTP (File Transfer Protocol)

- JSON (Javascript Object Notation)

- HTML (HyperText Markup Language)

- CSS (Cascading Style Sheet)

- IE (Internet Explorer)

- CLI (Command Line Interface)

- GUI (Graphical User Interface)

- ECMA (European Computer Manufacturers Association)

- W3C (World Wide Web Consortium)

- DOM (Display Object Model)

How the Internet Works in 5 Minutes

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7_LPdttKXPc

Server, Client, Request, HTTP

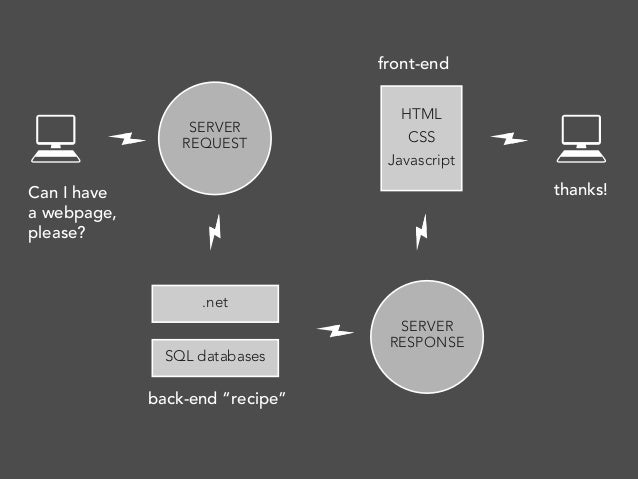

The internet as you know comes down to requests and responses - you send information out, and based on the info you send, you get information back.

TCP/IP Suite

The internet is a massive network of computers, with an agreed set of languages or protocols that describe how they communicate. This is often called the TCP/IP Suite.

The TCP/IP suite consists of 4 Layers:

- Application Layer - deals with the sharing of data

- Transport Layer - deals with how ports are assigned

- Internet Layer - deals with addressing and routing

- Link Layer - deals with physical infrastructure

Don't worry about this too much, this isn't a networking course but a basic understanding is essential as a web developer, though you will typically spend most time working on the Application Layer.

HTTP 101 (Application Layer)

HTTP is the most common protocol we'll work with. It stands for "Hyper Text Transfer Protocol", it allows for communication between a variety of different computers and supports a ton of different network configurations. To make this possible, it assumes very little about a particular system, and does not keep state between different message exchanges.

Read this as: "HTTP makes it easy for many different computers to talk to each other."

This makes HTTP a stateless protocol.

Let's define the following vocabulary:

- Host - a computer or other device connected to a computer network; host may offer information resources, services, and applications (via computer code!) to users or other computers on the network. Often used interchangeably with the term server.

- Ex: servers and web services

- Client - the requesting program in the client/host relationship; the client initiates an HTTP request message, which is serviced through a HTTP response message in return

- Ex: browsers, terminals, SQL clients

To sum it up, communication between a host and a client occurs via a request/response pair. The client initiates an HTTP request message, which is serviced through a HTTP response message in return. We will look at this fundamental message-pair in the next section.

Now, we're making this really simple, just to give you the big idea - there are a ton of intricacies that go into getting your request message to the right place and delivering the information you requested. We'll go into more detail today and over the rest of the course.

Text From Tuts +

Note that you will have seen HTTPS used on websites, this is the secure version of the http protocol and is used when transmitting sensitive data. It uses encryption and is more secure but is slower.

How to reach a specific server

All computers on the internet have a unique numeric address. This is the way computers find "each other" when communicating. You may recognize the format below - it's an IP address:

123.123.123.123

Traditionally, IP addresses are composed of four bytes of data separated by periods. Since four bytes only offer around 4.3 billion unique IP addresses, they've all but run out. A migration is underway to IPv6 that uses 16 bytes - or 4.3 billion to the power of 4 - that would provide an absurd 42 undecillion unique combinations.

IPv6 addresses are represented as a colon-separated chain of four base-16 digits. For convenience groups of zeroes are squashed. IPv4 addresses neatly fit inside IPv6 addresses.

2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334

2001:0db8:85a3::8a2e:0370:7334

::ffff:192.0.2.128

IP Addresses to domains (Internet Layer)

Of course, these numbers are hard to remember, and are not really human-friendly. Can you imagine if website addresses had to be given this way? Instead of commercials on the radio saying "go to OurWebsite.com", they'd be saying "go to 12.14.142.231" and repeating it five times just to make sure everyone got it!

So what was needed was a way to translate real names in to those numbers. This is why we have domain registrars - basically, you reserve the name, and at the domain registrar, your domain name is pointed to the server's particular unique address.

When you type a website domain in to your web browser (or other internet capable app), what happens is a "DNS Lookup" of that particular domain's IP address, so your computer can actually connect to it. DNS stands for "Domain Name System", and it's the way that Internet domain names are located and translated into Internet Protocol addresses.

| Domain Name | IP Address |

|---|---|

| apple.com | 17.172.224.47 |

| facebook.com | 31.13.65.1 |

| google.com | 216.58.192.46 |

So when you go to apple.com, your browser asks a DNS server "what is the IP address of apple.com?" The DNS server responds with "17.172.224.47", and the browser can then connect to 17.172.224.47.

The best example I've heard is to think of DNS like a phonebook. The domain name is your favourite restaurant but the IP Address is the telephone number you need to contact it. Fortunately, your browser, the telephone operator is smart enough to do the lookup for you.

How DNS Servers Look Up IP Addresses

Your computer looks up IP addresses for domains by asking the nearest DNS server - typically, the local wifi router. The wifi router will not know the IP address unless it was previously looked up, so, the router will further up the hierarchy to your internet service provider's DNS server.

Often, another ISP customer has already requested the domain lookup and the IP address is cached for a while, allowing a quick response.

Otherwise, the lookup is escalated to the top level domain (TLD) registry that has a list of registrars per domain. The registrar is the final authority that resolves the IP address.

The response is passed back along the chain and cached at each step to speed up future lookups.

Note: The caching along the chain is great for performance. However, changing the IP address of a domain name will not propagate to all visitors until cached lookups expire - typically 24hrs.

Ports (Transport Layer)

Whilst we're using our telephone analogy, it's worth mentioning ports. These are the channels that a server agrees to listen to and hence where a client must send their messages and wait for their responses. In the old days, when telephone calls used to go through an operator, they would connect callers across ports, this is a good way to think about it. On the web this is generally hidden from you as ports defaults to port 80 for http and 443 for https but when we're turning our own machines into servers later down the line, we'll be setting the ports.

Client and server communication

All client-server protocols operate in the application layer. The application-layer protocol defines the basic patterns of the dialogue.

A server may receive requests from many different clients in a very short period of time. Because the computer can perform a limited number of tasks at any moment, it relies on a scheduling system to prioritize incoming requests from clients in order to accommodate them all in turn. To prevent abuse and maximize uptime, the server's software limits how a client can use the server's resources. Even so, a server is not immune from abuse. A denial of service attack exploits a server's obligation to process requests by bombarding it with requests incessantly. This inhibits the server's ability to respond to legitimate requests.

Example

When a bank customer accesses online banking services with a web browser (the client), the client initiates a request to the bank's web server. The customer's login credentials may be stored in a database, and the web server accesses the database server as a client. An application server interprets the returned data by applying the bank's business logic, and provides the output to the web server. Finally, the web server returns the result to the client web browser for display. In each step of this sequence of client–server message exchanges, a computer processes a request and returns data. This is the request-response messaging pattern. When all the requests are met, the sequence is complete and the web browser presents the data to the customer.

Taken from Wikipedia

The World Wide Web vs. The Internet

The Internet is a Big Collection of Computers and Cables

The Internet is named for "interconnection of computer networks". It is a massive hardware combination of millions of personal, business, and governmental computers, all connected like roads and highways.

No single person owns the Internet. No single government has authority over its operations. Some technical rules and hardware/software standards enforce how people plug into the Internet, but for the most part, the Internet is a free and open broadcast medium of hardware networking.

The Web Is a Big Collection of HTML Pages on the Internet

The World Wide Web, or "Web" for short, is a massive collection of digital pages: that large software subset of the Internet dedicated to broadcasting content in the form of HTML pages. The Web is viewed by using free software called web browsers. Born in 1989, the Web is based on hypertext transfer protocol, the language which allows you and me to "jump" (hyperlink) to any other public web page. There are over 65 billion public web pages on the Web today."

- Taken from About Tech

Elements of a URL

URL stands for Uniform Resource Locator, and it's just a string of text characters used by Web browsers, email clients and other software to format the contents of an internet request message.

Let's breakdown the contents of a URL:

Note. Draw the following on the board

http://www.example.org/hello/world/foo.html?foo=bar&baz=bat#footer

\___/ \_____________/ \__________________/ \_____________/ \____/

protocol host/domain name path querystring hash/fragment

| Element | About |

|---|---|

| protocol | the most popular application protocol used on the world wide web is HTTP. Other familiar types of application protocols include FTP, SSH, GIT, FILE, HTTPS |

| host/domain name | the host or domain name is looked up in DNS to find the IP address of the host - the server that's providing the resource. This may include a subdomain, which in it's simplest sense is like a folder on the server. www is actually a subdomain and is often used by default on servers, allowing you to omit it in the URL sometimes. |

| path | web servers can organise resources into what is effectively files in directories; the path indicates to the server which file from which directory the client wants |

| querystring | the client can pass parameters to the server through the querystring (in a GET request method); the server can then use these to customise the response - such as values to filter a search result |

| hash/fragment | the URI fragment is generally used by the client to identify some portion of the content in the response; interestingly, a broken hash will not break the whole link - it isn't the case for the previous elements |

The Schema above is from Tuts +

When someone types http://google.com in a web browser, a new cycle resulting in an HTTP Request/ Response is initiated. Essentially, your browser is saying:

"Hey, give me the information located at the web address 'google.com'"

When the user press enter in the url input in a web browser, a GET request will start.

Anything after the ? is considered a parameter - information you're also giving to that web address in the querystring.

Note. Try a Curl request. curl -i https://github.com to show the header info

In the response, the HTTP version is provided, which in this case is 1.1.

The rest of the lines are HTTP headers, which do things like: tell the webserver what website to retrieve, based on the domain (Host:); report the user-agent and acceptable encoding and language; and other browser-specific options.

Notice the Content-Type is text/html and we can see the returned html in the body

Note. Try a Curl request with a json data type, replace jeremiahalex with your github username. curl -i https://api.github.com/users/jeremiahalex

Responding to a request - Intro

Once this request reaches the server, then this server will return a response to the request emitter.

HTTP responses are similar to HTTP requests in the way that they are text based and contain HTTP headers and status. Look on the first line above, again - the HTTP response returns the HTTP status code. This code is very useful for developers working with request/response cycles.

They come as three digit numbers and dictate whether a specific HTTP requests has been successfully completed. Responses are grouped in five classes, with the first digit determining the higher-level categorization:

- 1xx Informational

- 2xx Success

- 3xx Redirection

- 4xx Client Error

- 5xx Server Error

After the status code, some server headers are sent, including information about the type of server and software it’s running. Next, the body of the response contains the data we requested, which is generally HTML, CSS, Javascript, or binary data like an image or PDF.

Since HTTP is a text-based protocol, it’s easy to make HTTP requests manually

Some text taken from One Month

Server-side vs. Client-side

Once the request <--> response cycle has been executed, the web browser is in charge of interpreting the data received and showing it to the user. Looking more closely at the types of computer languages and markup that's involved:

The server contains code - Ruby, PHP, Java, even JavaScript - that processes your request. Depending on the contents of your request, the server will execute different files on the server that contain code. Then, the server will return a particular set of information and data.

The information and data received is usually packaged in an HTML document with some CSS and JavaScript files. You may also get a PDF, image, and/or other file types. The location of the resource is specified by the user using a URL.

The way the browser interprets and displays HTML files is detailed in the HTML and CSS specifications. These specifications are maintained by the W3C (World Wide Web Consortium) organization, an important standards organization for the web. The JavaScript language specification is published by a technical committee (TC39) at the ECMA organization.

Taken from HTML5Rocks

Web Browsers

As web developers we'll be spending a lot of time in web browsers. Web Browsers are typically used to access the www, they receive content from servers and then they present it back to the user in accordance with agreed standards. However, they do have different rendering engines and often different interpretations of standards, so different websites will often look quite different on different browsers. Some browsers do use the same rendering engines, for instance Chrome used to use the same engine as Safari called WebKit but as of Chrome v28 they started their own called Blink. You can find lots of information online about the different engines and what to expect but typically you'll need to test your websites on all the major browsers if you want to be sure of what your users are seeing.